Sandarne, Sweden, April 10th, 2022

My first real contact with a higher mountain was when I was 9 years old and our family vacationed for a week in the mountains. We arrived at the foot of Östfjället in Gräftåvallen on a scorching summer day. I immediately took a trip up the mountain and something struck me strongly. The experience of the mountain just continuing up higher and higher felt unreal and powerful.My first real contact with a slightly higher mountain was when I was 9 years old and our family vacationed for a week in the mountains. We arrived at the foot of Östfjället in Gräftåvallen on a scorching summer day. I immediately took a trip up the mountain and something struck me strongly. The experience of the mountain just continuing up higher and higher felt unreal and powerful. It gave me a feeling of rapture that I have continued to carry with me.

Since then, I have been fascinated by and longed for the mountains, read about them, watched movies, and followed various adventurers on off-piste skiing and climbing. The Swedish Skiing magazine Åka Skidor was the first magazine where I could meet adventure.

The strongest experiences of nature as a teenager were outside the slopes when we skied downhill. As an adult, I have hiked, done summit tours, and run in the mountains and always feel that I want to experience more mountains. What is it about mountains that fascinates and attracts? What motivates so many people to want to do difficult, challenging, and sometimes life-threatening things in the mountains?

A possible explanation can be found in the biophilia hypothesis - as I have mentioned in some previous posts. Since humans have evolved in nature, our psychology and physiology have adapted to nature and its conditions. The fact that we are created in this way makes us long for and need nature to thrive, experience, be challenged, develop, and increasingly recover from our everyday lives.

According to Henriksson's etymological dictionary, the word motivation comes from Medieval Latin motivum, which means an action that sets in motion, driving cause. Of motivus which means to set in motion and movere which means to move and disturb.

Nordstedts Swedish Synonyms and Expressions writes: Motivation - summary of motives for a will act, action basis, motivating reason, driving force, will direction.

As I understand it, we can see motivation as the reasons for something we do, i.e. for a behavior. When we behave, there are reasons for these behaviors. Motivation is the summary of these reasons. What we don't do, we are not (sufficiently) motivated to do right now or we do not have the opportunity. The causes of behavior are found in our genes, the physiology we have, our learning history, and our current context. The prehistoric human probably sought out of his cave in the morning to get light, we have learned that (usually) it is enough to press the light switch to get light. History and context determine the current behavior. The driving force and function of the behavior may be the same even though they are different behaviors.

As a result of human evolution, we have a number of more or less basic common needs that concern our immediate survival. Some needs concern our survival in the slightly longer term. In addition, we have needs that are more about survival in a much longer perspective, perhaps over generations, which have been particularly important for our enormous adaptability and made it so that among all human species, only we survived, i.e. it is only Homo sapiens who have survived - at least so far. A longing to see what lies beyond the next mountain top, on the other side of the sea, or at the bottom of the deepest ravine has made humans spread across continents. The longing for challenges and to experience new things has driven us to learn how to handle new situations.

Abraham Maslow is the first person that comes to mind when we describe needs and motivation based on different categories or levels. He presented his need model in the 1950s. Someone in marketing picked up Maslow's categories and arranged them in a hierarchy, which later became known as Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

Most people who have studied psychology have come into contact with the hierarchy of needs, and the strength of it can partly be attributed to the fact that it feels immediately and intuitively right. In psychology, we usually call it face validity when a theory or hypothesis is directly perceived as valid and true. Later research has shown that the prioritization described in the hierarchy of needs is far from always accurate and that we can be driven by satisfying needs at several different levels simultaneously or prioritize needs in other ways based on personality, history, and cultural differences.

It is also clear that we consciously put ourselves in situations where our basic needs are put at stake to reach higher needs. We may quit a safe and well-paying job to find something more meaningful in the long run by furthering our education. Some people engage in challenging adventures where they will freeze, starve, experience pain, be exhausted, and perhaps even risk their lives. These behaviors go against our immediate needs but have likely been essential for our species' long-term survival. These needs, like other human characteristics, have varied with chance and caused us to prioritize different needs and behaviors in our lives.

Individual needs that become important to you or me can be expressed as values. If we live in a way that is not in line with our values, we will experience a lack or a dissonance that can eventually lead to various symptoms. If the feeling becomes strong enough, we will feel more motivated to change. If we start moving more in our valued direction, we will feel a greater sense of coherence and meaning. Another way to express it is that we become more integrated and have stronger self-esteem when values and behaviors align better.

Scott Jurek had a career in the late 1990s and 2000s as one of the world's best ultra trail runners, and his biggest successes were mainly in races in the mountains. He grew up under difficult circumstances but always felt comfortable in nature. When he discovered his talent for running long distances, he found purpose and meaning in his life through ultra running.

After his elite career, he continued to run some races and give lectures here and there without much purpose or plan. The training was at a low level for him, and he performed far below his potential, and he had a hard time finding any new meaningful direction in life. His wife Jenny grew tired of his listlessness and questioned what he really wanted with his and their shared life.

After some thinking, he realized that he still had both the opportunity and the will to make more of an impact in running. He asked Jenny if she could support him in an FKT or Fastest Known Time on the Appalachian Trail. That is, to make an attempt to be the person who has taken the whole Appalachian Trail on foot in the fastest time, one of the most famous and tough hiking trails that goes along the Appalachian mountain range through the USA.

Jenny replied that she wanted to help him, and they made a joint project of it. For almost eight weeks, partly day and night, they fought together, Scott on the trail and Jenny with stocking up and finding their way with their mobile home on small hidden forest roads. On July 12, 2015, at 2:05 pm, he stood at the top of Mt Katahdin. It took Scott 46 days, 8 hours, and 7 minutes to complete the 349-mile, largely rugged hiking trail. He beat the old record by 3 hours, averaging over 75 km per day.

They truly accomplished the run together, without Jenny, Scott wouldn´t have standed a chance to succed. After the successful FKT (Fastest Known Time) record, they collaborated to write a book about their experiences and how it brought them closer together. The book is called North, symbolizing both his northward run on the trail and perhaps most importantly, finding his True North, meaning a life more aligned with his core values, where running and joint projects with his wife Jenny could take a more prominent place in life.

In an episode of the Psychology podcast, Scott Barry Kaufman, in a discussion about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, suggests the existence of a third category of motivation based on values. This is consistent with the approach in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, where we explore and emphasize our values. When there is a gap between values and behaviors, we take small steps in a valued direction.

If your value is to prioritize your health and you believe you can manage a short walk every day, awareness of each small step towards your valued direction can increase the value of each step. It is easier to focus on the process here and now, and this increases the likelihood that the behavior will be reinforced, compared to only focusing on the value of the end goal.

Starting with something small and continuing with it over time will yield significant results. A 20-minute walk each day may not seem like much, but it is entirely in line with a value of exercising a little every day. The result doesn't actually matter, but over a year, it amounts to 122 hours of exercise or about 72 miles, and it makes a difference for your health.

In the book The Sweet Spot, psychologist Paul Bloom describes how we can be motivated in many different ways and advocates for a pluralistic view of motivation. We have the hedonistic tradition, where we are thought to be driven only by pleasure and pain, and the eudaimonic tradition, where we are motivated by factors that bring meaning, such as community, competence, autonomy, altruism, and curiosity. Based on his reasoning, I believe that a pluralistic motivation model could look like the one in the image below.

On the right – Values and experiences that’s important to you

In the model, value-based motivation becomes the overarching reason for why we do something. Goal-based motivation lays the foundation for the action itself, helping us know what to do and what to focus on. Experience-based motivation is something we create along the way when we engage in the process and make contact with experiences and feelings of meaningfulness and living a life where we feel things, where feeling and experiencing becomes meaningful in itself.

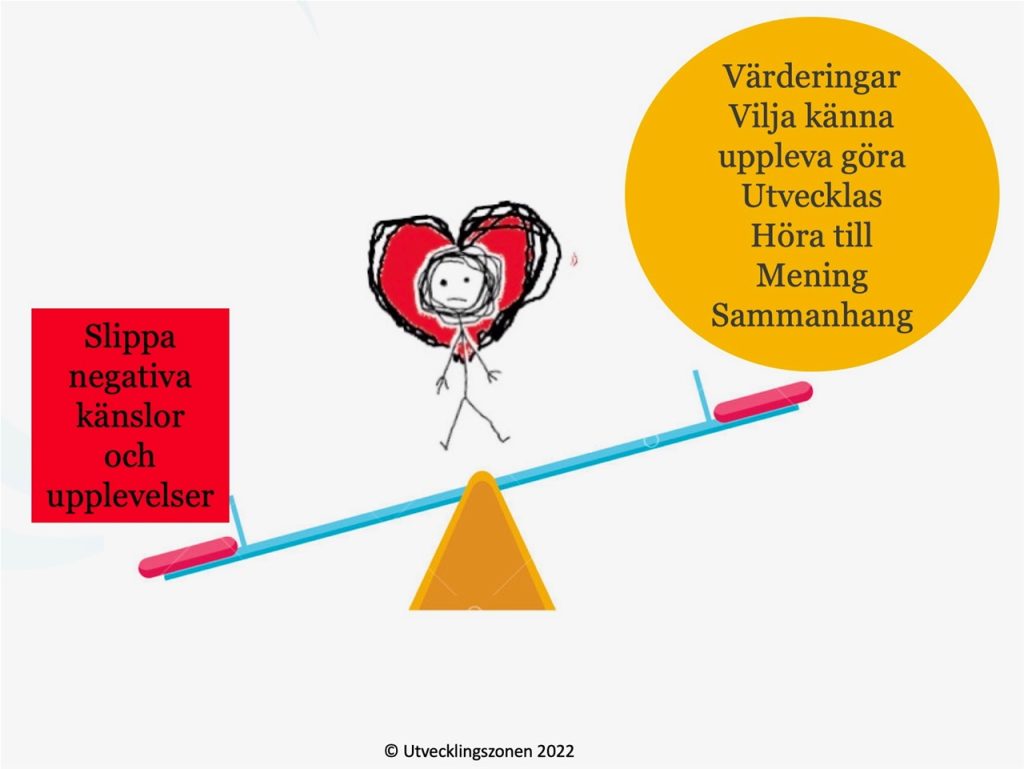

I often use the metaphor of a seesaw or balance scale to illustrate motivation in my clinical work. On one side of the scale is everything that is valuable to us and that we want to achieve, feel, experience, and stand for. On the other side are all the things we want to avoid feeling and experiencing, which keep us stuck in situations and emotions we don't enjoy.

The seesaw model includes both hedonically-driven and value-driven motivation. It is simple and tangible and is intended to illustrate the difference between short-term, negatively reinforced avoidance and long-term, positively reinforced approach. I have recently started using the other model with the three different types of motivation. It is not as obvious, but I think it adds useful aspects of what motivates us.

I love hiking different mountains in both summer and winter, enjoy paddling and swimming in various bodies of water, and long to run long distances on new trails. These are all different ways to spend a lot of time in nature, to recharge mentally and satisfy curiosity and a thirst for adventure.

Sometimes a large part of these experiences are driven by goals such as preparations for different races, the goal of swimming in different bodies of water, completing a certain distance, or being able to run all the way up a mountain. It helps to have external goal-driven motivation to get out and do what I've decided to do. But in the background, it is always a part of my values to spend a lot of time in nature in motion, and almost always it is possible to connect with the experience-based inner motivation.

Some of the greatest nature experiences I have had are related to races I have run in the mountains, some challenging peak ascents, and some powder skiing in really big mountains. Besides being in the mountains, the common denominator is that the presence in certain moments has been total, and I have lost myself in the experience and feeling of flow. Perhaps that is why the mountains have become so special. Maybe it's because the top of a mountain is such a clear goal, that it is a strong feeling when we reach the highest point. Perhaps it is because it is innate in our genes to feel positive emotions when we stand on top of a mountain and can orient ourselves in the surroundings.

P.S. To be really honest, what I long for the most right now is my daily running, it's an even greater driving force connected to the need to be in motion in nature. But three herniated discs in my lower back still prevent me from doing it.